2019 will go down in history as the most difficult planting season for North American farmers, with over 10 million acres of crops going unplanted due to extreme weather conditions. At the same time, farmers in Punjab, in India, are experiencing rain showers almost every month and, for the first time in its history, more humid air is leading to greater pest infestations.

The effects of climate change can be felt daily, especially by farmers, but very few solutions have been discussed to address this catastrophic threat. However, there is one, widely unknown solution to reducing the amount of greenhouse gases trapped in the atmosphere: agriculture.

Reducing tillage, expanding crop rotations, planting cover crops and reintegrating livestock into crop production systems have proven to reduce agriculture’s own footprint as well as capture the excess carbon generated by other industries. This captured carbon is then converted into plant material and/or soil organic matter, improving soil health and increasing the ability to produce food on the land in the future.

These practices often reduce input costs as well. Adopting these practices seems like the obvious choice, so you might be curious why a majority of farmers globally have continued using traditional agriculture practices.

We have an answer to that. As lifelong farmers in two different geographies, we reflect on our difficult journeys as we begin to adopt these management practices and the multiple barriers we are facing along the way.

Pursuing a greener production system requires farmers to embark on uncharted territories with no guarantee of immediate success. Farmers usually experience decreased yields during the transition process, as they gain the required experience to learn and perfect the implementation of more regenerative and beneficial practices.

A decrease in production poses a difficult financial challenge to overcome – especially for Indian farmers, who already have a hard time competing with developed nations, where subsides have artificially driven down the price of agriculture produce. The government’s import and export policy decisions, which heavily favour consumers over producers by keeping prices artificially low, also have a large impact on the ability of farmers in India to adopt more sustainable practices.

In the US, farmers face systematic financial challenges, like difficulty accessing sustainable inputs at a reasonable price. Farm input suppliers are highly concentrated, exerting significant pricing power and making systems innovation unattractive to their bottom line. The resulting high operating costs, along with the required upfront costs, increase the need for access to external capital. However, capital is most available to farmers with the most traditional, low-return production systems. In short, generally the systems that are least regenerative, emit the most greenhouse gases, and result in the most land degradation, are the most likely to have access to capital.

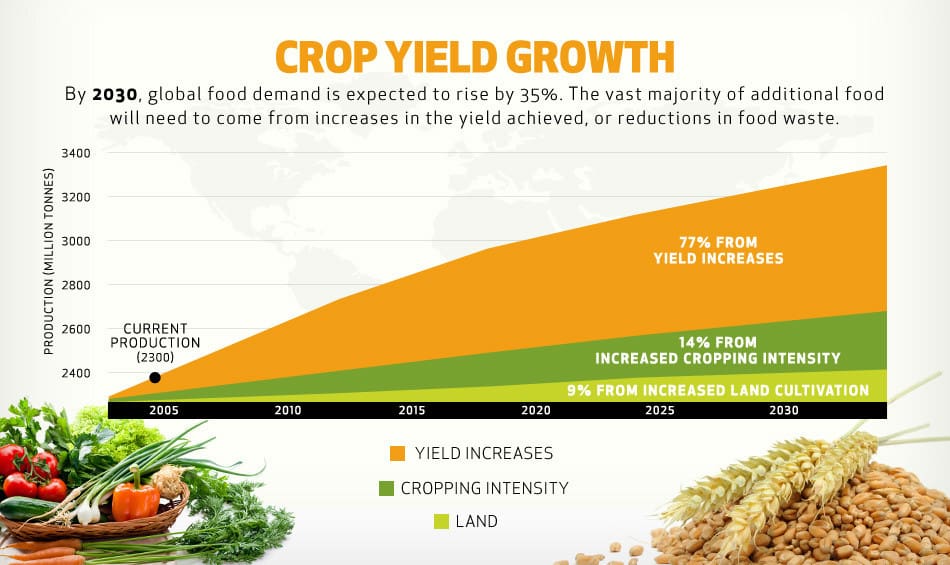

Subsidies and regulations play a role in the availability of external capital, since these cash streams serve as a de-risking mechanism for finance players. The US government’s policies, such as a federally subsidized crop insurance, focus on ensuring a stable food supply rather than on the nutritional value or environmental impacts of the food being produced. This focus on quantity over quality is the same in India, where decision makers have rolled out an initiative to increase food production by the year 2050. This goal has become the cornerstone of India’s national policy and the metric for measuring farmers’ success.

Another key challenge we face is the lack of data and available information on these management practices as well as the lack of ways to measure which of these new, innovative systems store the most carbon in the earth’s soil. Such a tool would open the door to private parties compensating farmers for sequestering carbon.

Accelerating Climate Action

In the meantime, governments’ regulations, along with growers’ low profit margins, stifle farmer innovation, limiting the ability for new, creative thinkers to join the industry or for current farmers to test new practices.

For example, subsidized crop insurance in the US inflates the value of farmland and locks producers into a low risk, low reward system, making it hard for new smallholder farmers to enter the business or current farmers to walk away from the easy revenue.

Additionally in the US, the tax code makes it financially efficient to sell or exchange farms and farmlands only after death. Also, farmland investments may be used to shelter gains realized on non-agriculture real estate, further increasing the barrier to entry.

In both the US and India, there is a lack of financial incentives for farmers to pursue innovation, while public funding for fundamental research and the application of research to agricultural practices, have been reduced in real terms.

Starved of funds, the public research system has taken the easier path and focused on identifying ways to maximize farm yields through mono-cropping and chemical usage, both of which increase agriculture emissions. This research further dissuades farmers from adopting sustainable practices.

One way to incentivize farmers to focus on increasing soil health is through de-commoditizing production and making it easier to identify and track producers, as food makes its way from farm to table. Doing so would unlock consumer demand as an incentive for greener farming. If consumers are willing to pay a higher price for food products that have been grown in an environmentally friendly manner, the economics of the system could be turned on its head.

Unfortunately, US crop buyers currently blend and commoditize production, leaving no pathway for consumers to reward farmers for establishing more favourable production systems. In India, where disposable income is fairly limited, increasing the price of foods could limit individuals’ ability to purchase foods, amplifying the fear of food inflation, a problem the government dreads.

As we have experienced firsthand, farmers face a variety of misaligned incentives when trying to adopt sustainable management practices – some of which require the whole ecosystem of actors to work together to overcome.

Each country, climate, and plot of land poses their own set of challenges, and it is clear there is no “one size fits all” solution. However, addressing these barriers is critical to unlocking agriculture’s ability to solve a portion of the climate change problem. We haven’t heard of a more compelling solution, have you?